I spent four short days in Poland, making my way from Warsaw to Krakow. I have seen the history of wartime Poland, I listened to the stories of a Righteous Among the Nations, and I caught a glimpse of Jewish life in Poland today. All these experiences, together, came to form a kaleidoscope image of modern-day Poland - and this is my attempt to decipher it. I thank you for coming on this journey with me.

As I walk on the rail tracks on my last day in Poland, my entire body aches. Shoulders slumped, back bent like a question mark, hands twisted so tightly they start to resemble twigs, I trudge through the cold, sharp air, eyes locked on the ground, waiting for the end.

I think about the bus that awaits me, and the cup of hot tea from the canteen just down the road. I think about my mom and dad, about gentle hands running along my back, untying all these knots. I think about love.

And then I raise my eyes and look around - and I realize that for over a million of my brethren, there was no escaping this walk. The end that followed this place meant only one thing: death.

I straighten my back, pull my shoulders up, and continue walking through Auschwitz-Birkenau, trying to understand.

I am 29 years old, and this is my first time in a death camp. And I am completely, utterly lost.

Most Jewish kids in Israel and North America come here, to Poland, on March of the Living when they are 16 years old. Most of us have already taken in countless hours of learning about the horrors, of looking at pictures of twisted, naked bodies, of memorizing the names of death and work and concentration camps. Most of us have become desensitized, numb from the atrocities, from the little lapses of judgement that have to occur in order to allow for a catastrophe of this magnitude to occur.

And yet, I find that every step here hurts, both emotionally and physically.

I find that my eyes are burning from unshed tears, and when those do spill, it hurts only marginally less.

I find that I do not know what to think or feel, that I am struggling with emotions all day, only to lose myself in a bit of vodka and a deep, dreamless sleep at night.

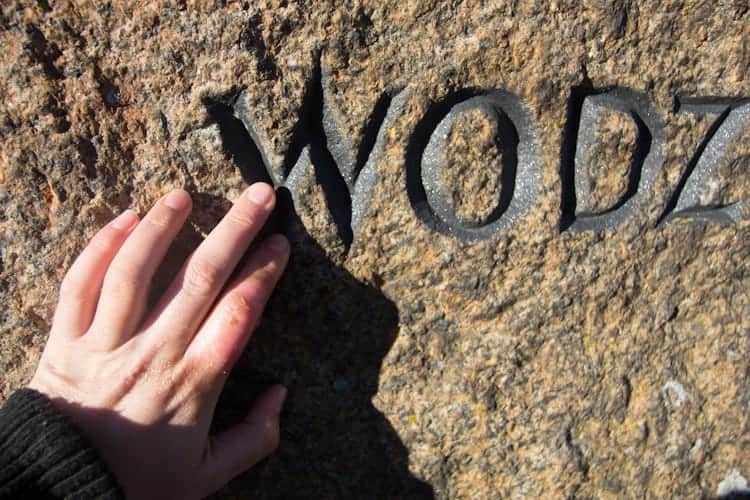

I find a Jewish tombstone in Plaszow, broken and discarded. I find a see-saw among the bushes, which are growing wildly from years of human ashes. I find the place where the parents of one of my travel companions went after the war ended, where they got married and tried to rebuild their lives, only to escape Poland and their memories altogether after a few short years. I find the shed where another travel companion's mother was during her days in Auschwitz.

And then, I find my ancestors. In a little shed on the outskirts of Auschwitz 1, I step into a room full of large, hanging books. People are walking around, flapping through the pages, staring intently; they are looking for their loved ones, the names of those who perished as a result of the Nazi occupation of Eastern Europe and the Holocaust.

I absentmindedly scroll through, trying to find a familiar name in over 6,000,000 Jewish victims. I know no one - no names, no dates, no towns. So I call my mother, asking for advice. Together, we leaf through the pages, looking for a glimpse of recognition, looking for hope... until we find it.

We find Liza Dvorkind, who my mom is named after, born in 1912, murdered in Borisov, Belorussia when the Nazis entered her town on their death journey to Russia. We find Dvorkind Simhon and Simah and Morris and Zalman, who were born in 1880 and 1890 and lived full lives until the Nazis entered their town on their death journey to Russia. We find Dvorkind Morris, born in 1928, who had only a glimpse of a life before he was shot down at the age of 13 when the Nazis entered his town on their death journey to Russia. We find Dvorkind Malka, who was just 2 when she was murdered in the arms of her mother, Liza, when the Nazis entered her town on their death journey to Russia.

With my father on the phone, and the help of my grandfather later, we find Rukhl Printz, 1869, from Kulchiny, Ukraine, killed during the Nazi occupation of Ukraine. We cannot find when she was born, or when she was killed. We cannot find her husband, Shmul-Idl Printz, 1869, who lived in Kulchiny but was born elsehwere. We find Rakhil Printz, 1876, from Starokonstantinov, Ukraine, but none of her realtives - her husband Chaim-Yossif Printz, and their children Mark and his sister Liza are gone without a trace, killed during the Nazi occupation of Ukraine.

And by finding them, their names, a trace of their lives, for the first time in this death camp, I feel found.

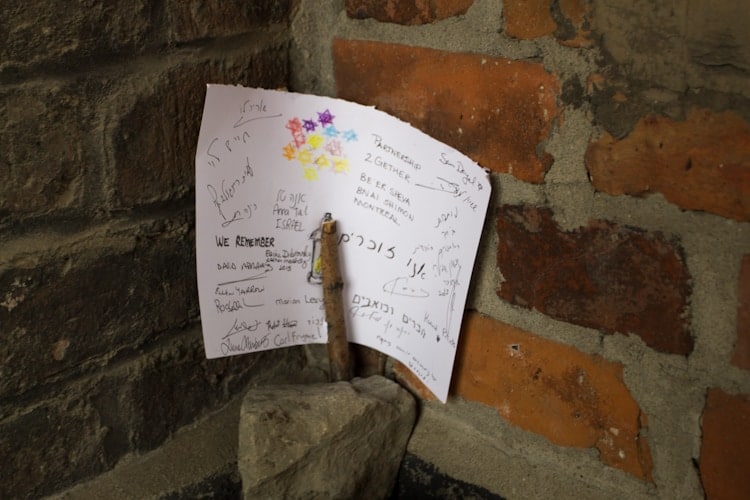

We are sitting in a brightly lit room in the Jewish Community Centre in Krakow. People are laughing all around us, flirting and making new friends, the wine is flowing and the conversation is easy. I am speaking Russian to a Ukrainian girl who has been studying in Krakow for five years. Though she knew about her Jewish roots her whole life, she was never raised Jewish for fear it would make her a target for discrimination, abuse, and ridicule; it was only when she was 16 that she took her father's (very) Jewish last name as her own. And yet here she is now, six years later, living a Jewish life in Poland.

She is not alone. All around us are young people, not one of them more than 30, who have recently discovered their Judaism. They have all embraced it, and are trying to help their siblings grapple with this new-found identity. They are also still learning, trying to discover for themselves what it all means to be Jewish - in Poland, the land where millions of us have perished, where good, old-fashioned antisemitic myths still persist, where you cannot walk a mile without being reminded that you're different.

And yet, they choose it anyway.

By sitting in this room in Krakow, listening to their stories, feeling their joy and passion over finally finding a piece of the missing puzzle, I, too, feel found.

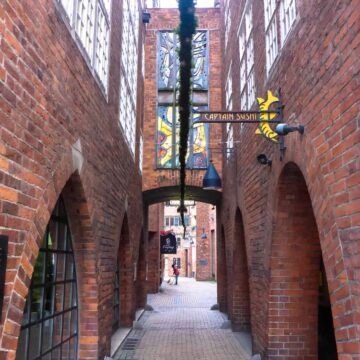

I am in a dark bar room in the underbelly of the Stalin building in Warsaw. There are young people all around me, engaging in those sorts of things you do in dark bar rooms: kissing, speaking to each other in overly-loud tones, looking intently into each other's eyes. I am drinking a dry local cider, talking about Israeli politics. I, too, am doing those things you do in dark bar rooms: speaking too loudly, gesticulating too animatedly, making too much eye contact.

Then, at the table next to us, I notice a pretty young woman. She is the same woman who, just 24 hours ago, told us about the Jewish revival in Warsaw. She is a leading figure in the local Jewish Community Centre, and the face of the campaign to rekindle a Jewish flame in Warsaw. She is beautiful, charismatic, and, like me, prone to eye contact and gesticulating and passionate speeches. She is also drinking with a friend in this dark bar room in the underbelly of the Stalin building in Warsaw.

But unlike me, she is not talking about Israeli politics. Right now, she is not contemplating what it means to be Jewish in Poland. She is not grappling with her identity, or marching through death camps, or finding long lost relatives. She is not struggling.

Instead, she lives with those memories, that knowledge, those ghosts every single day. She embraces her torn history and tries to live her life to the fullest in the only way she knows how: honestly. She lives in Poland, and loves Poland, and probably hates it, too, on some days.

And at this moment, looking at what seems like true acceptance of one's fate, I feel found.

I have debated whether I want to talk about modern-day Poland and my experiences there through a recipe. In the end, I decided I wanted this to be an opportunity for discussion, rather than a chance to gawk at images and move on. So I hope that after reading this, you will take the time to comment, reflect, and offer some insight into understanding that which cannot be understood.

I also wondered whether I want to discuss my experience in the death camps, the ghettos, and the streets where so much of my ancestors' blood was spilled separately from my findings of the beauty of Krakow, the vibrancy of Warsaw. But I decided that just like you can't separate the experience of the Holocaust from the reality of Modern-day Poland, so you shouldn't treat them as two different experiences.

If you've gotten this far, congratulations - and from the bottom of my heart, thank you.

I hope you have gotten something of this experience.

Kimberly says

Thanks for the post, Ksenia. It brought back a lot of memories for me. I went to Krakow in 2009- I was barely 21. 3 friends and I spent a month gallivanting around Europe, and when we put together the itinerary, I demanded that Poland be included in some way. My mother's mother is a 1st generation American-born Polish Catholic who converted to Judaism to marry my mother's father, a 1st generation American born Austrian Jew. Their marriage didn't last long, and after two kids and years of fighting they divorced and my Polish grandma returned to Catholicism. They split custody of my mom, who has been confirmed, baptized, bat mitzvah'd and reads Hebrew. As a child, I didn't really internalize these histories and nationalities as it seemed to be favoring one side of the family over another. We celebrated Hanukkah and Christmas, and ate pierogis and gefilte fish (yuck). Both sides of my family history coexisted peacefully inside me, for the most part.

When we went to Europe, I initially did not want to go to Auschwitz, Berkenau, or any of the ghettos. I was young and thought it would "ruin" my happy vacation by leaving me a sobbing sniveling wreck. My friends, none of whom had Jewish heritage, wanted to go to see the history, to say they'd been there, and I told them they'd have to go without me. On the very night before they were to depart, I spoke with my mom. Being a mother, she told me she would support my decision either way, but gently reminded me that to not go would be disrespectful to both my ancestors that died in the Holocaust as well as my ancestors that successfully "made it out." To bear witness to the history would be the ultimate respect I could pay them. And so I went- thinking that this wasn't about me or my vacation, but about bearing witness to history.

The experiences you have described here very much struck close to home with me. Auschwitz did not reduce me to a pile of tears- if anything I was shocked by how peaceful and quiet the countryside of Poland could be. It seemed unfair to me that birds continued to sing, that sunlight continued to bathe Poland's countryside- I don't know why I had expected that nature give way and respect the atrocities that took place. That was the most striking part of my journey- the fact that there could be so much beauty and natural peace in places that held so much death. It reminded me that it is our duty to remember, because the birds, the sun, the ground will not. This idea that by going I was paying homage to those that made it out and those that did not, this idea of bearing witness- paired with the stillness and calm of the landscape, made the experience more than I could have imagined. My initial perception that it would be too much to bear, that I would have cried and cried seems so silly. It seems to me that to have done so would have turned the sites in to a sort of "Disney-like' gimmick of memory, rather than the resounding reality of how social memory actually lives with us. The past- personal, familial, or international- is something we all silently live with and deal with on our own terms- these places force you to internalize and respect these memories, allegiances, and questions of identity. You can't have one cathartic moment of tears and crisis and call it a day- it is something you continually process, come to terms with, and hold sacred. And it made me question a lot about myself and my identity- very much like in a manner that modern Poland does. What does it mean to have both Polish Catholic and Jewish ancestry? I read about Yedwabne and Poland's own dark history, and realize that identity is not stagnant or one-sided, that one can "own" both sides of a history without doing an injustice to either.

I thank you for the pictures. It reminded me of the awe inspiring beauty of these places that hold such darkness in their history. The dichotomy of beauty and death is what I will always remember most from my own experience, and you have captured it well.

kseniaprints says

Oh, Kimberly. First of all, I just want to say this is exactly what I was hoping for - to encourage others to share their own feelings, however, conflicted, about their experiences in Poland.

Your conflict rings so true for many people. I think that your family's history is what made your visit so much more special - as you said, you weren't caught in the trap of the Disneyfication of memory - instead, you were able to see beyond it and experience the place for your own, process it in your own way, and, precisely as you've so eloquently put into words, process overtime long after you go home.

I thought that writing this piece will put some sort of a stop to my processing. Instead, I feel like it just pushed me into a new level. I now find my mind constantly going back to those names, those books, and wondering - is that it? How can I make that memory experience more tangible, how can I bear witness and 'find' these people in deeper, more meaningful ways? Because as you've said, identity is multifaceted, and I believe that discovering that aspect of my family has uncovered a new part in my identity that I never thought to explore.

Thank you, once again, for your honesty and courage in sharing something so personal.

Elena says

Another one of your posts that made me cry. Thank you for sharing! I was in Auschwitz too and I couldn't come back to normal life for some days after what I've seen

kseniaprints says

It's a strange place... I found it angered me in more ways than it touched me. But, I guess that's the natural first steps in grief...

Nicole says

Thank you for sharing in your vulnerability. Reading your post led to some meaningful quiet reflection.

kseniaprints says

I am so humbled it could do that, Nicole. In my mind, that's the highest purpose of the written word! Thank you so much for reading.

Golum says

Hi Ksenia:

We took a tour of Eastern Europe in 1990.......Germany, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia & Austria.

It was an extremely interesting tour...my main reason was that it included a tour stop at Auschwitz. I had visited Dachau in 1975 but really wanted to see the "big kamp." Although not a Jewish tour it made the highlight stops...In Warsaw we saw the marker (at that time the ghetto had become a bunch of modern condos & apts.) ...and only a small marker noting the Warsaw Ghetto and the uprising.

In Krakow we saw "Swastikas" spray painted on the wall in the main town square.

It's interesting that at Dachau it was a very somber place...nothing for sale, just the open gates for your do-it-yourself tour and a small museum in the guard's quarters.

At Auschwitz we saw the main kamp only not Birkenau. As we walked in we had to watch for "neighborhood Polish kids" on big wheels riding around the kamp as if it were Disneyland (which in fact it is...being poland's largest tourist attraction). We walked past a lemonade stand, the Carmelite Nuns were hanging around all over the place, there were large numbers of palestinian supporters with flags protesting something, there was a gift store where they sold T-Shirts & Posters??????? Could anything be more wrong????

kseniaprints says

This is horrible! I have to say that this sounds much, much worse than my own experience at Auschwitz... However, your sense that the place has become Disneyland is precisely true (and it's something another commenter, Kimberly, referred to just below). I couldn't believe the crowds, or the lines to buy something at the canteen, or the gift shop... And the silent walk along the display cases was unbelievably macabre and wrong. To me, it felt like a mockery of memory and, frankly, something very offensive to those who perished.

However, I felt a lot of meaning in the Yad Vashem pavillion. It was practically empty of people, but the content spoke volumes. There was an exhibit of children's drawings that broke me, and videos of survivors that made me feel hopeful and surprised at the strength of the human spirit. I don't think it was there when you visited, but it was definitely the one redeeming quality of Auschwitz 1.

Birkenau was quite different. Desolate and vast, it felt exactly like what it was: a place over a million Jews and many others went to their death in the most horrible ways. I said a lot about it in this post, but I am honestly still shocked by how visceral and physical my reaction to this camp was. There was just something about it...

Thank you for sharing your experiences, however awful. I think it stands to teach us a valuable lesson about memorials, human greed, and its boundaries.

Alan says

Thank you for sharing what is an immensely personal, and emotional experience.

Having not had any real connection with this period of history or the land in which it happened (beyond a shared sense of horror at the reality of the crimes perpetrated there), I am in awe of you for being able to be so eloquent in your expression.

kseniaprints says

Thank you, Alan. It's a constant learning process, and I guess I'm grateful for getting the chance to experiment with my writing over something that was indeed so monumental and, in truth, that cannot be expressed in simple words.

Kellie MacMillan says

It seems like it's been weeks since you posted this but really only 6 days. I had mentioned in FB that I had read all the way through but didn't know what I wanted to say. I know what I wanted to say but just am not sure how to. This may sound strange but the only word that kept coming to my mind was how beautiful your story is. I have never been able to watch movies about the concentration camps, the obliteration of the Scots, mass graves in 3rd world countries or gladiator movies even the crucifixion. Although I know exactly what happened I am still and always will be horrified that these atrocities happened and continue to happen in the world we live in. i.e. ISIS. Personally, I had a person in my life that was horrifically awful and it was the worst and freeing day of my life when I was able to admit that there are just bad people in this world. I honestly don't feel I have the capacity in my heart to really believe this. I always still want to believe in hope and the best in people. Ksenia, you allowed me to see that death must have been beautiful to those poor people. I can't get so worked up and angry that bad people still are doing bad things to other people. I have such a simplistic world view but I'd like to think Canada has done things differently. I know that every single day of my life I have a chance to speak up for equality by using my heart and the love that makes up my being rather than by abuse, force or killing. There is no right or wrong way to view this and I'm not even sure I've said anything that matters but I thank you for telling the story and allowing me a chance to comment. Keep being yourself and share what's in your pure heart. You are amazing.

Berta says

This was such an interesting read!!

I grew up with all of the myths and stereotypes and jokes about Jews that are so common among Eastern Europeans. And yet, the more I learn about history, both personal and national, the more I realise what a significant role Jewish people played, and that their mark can never be erased. (Moreover, I probably have some Jewish blood in me too, although that is too hard to prove given that so few ore-WW2 records exist.)

Thank you for sharing your story and helping me develop a more open-minded and understanding view of the world and the different people that live in it 🙂

josh berman says

as a religious jew returning to krakow every year,and establishing dialouge with polish men and women,what are ur feelings?can auschwitz happen again,as me and u are witness to a fast changing world with genocidal smell still in the air.

kseniaprints says

Hello Josh, if I understand correctly, you are a religious Jew who returns to Krakow annually to promote dialogue? First off, I think that's an incredibly worthwhile cause that has implications on so many levels: the Jews in Poland, people who are just discovering their Judaism, the gentiles in Poland, and religious minorities outside of Poland as well. I salute you for your efforts, and would love to learn more - you can send me an email at info at immigrantstable dot com.

As for whether or not I think that Auschwitz can happen again.... That's a very, very difficult question. Of course I want to say NO. And on many levels, I dont believe that Jews would ever face that level of prosecution again. But I see what is happening around the world towards refugees, and minorities, and the difficulties that religious group face in various countries... And I seriously, genuinely worry. Maybe not for the Jews, but for our non-Jewish brethren? Very much so.

Maria says

I read through this out of obvious historical interest (though my studies touched more on Italian fascism, and the coincidence of the Polish journey bumped up against your equally short Argentine trip. A professor friend in

Buenos Aires, a boomer like me (we are almost exactly the same age) was in a thoughtful mood when we first met in Paris at an academic event.

Friend's parents were Polish Jews from Warsaw, who somehow got out of there and emigrated as young adults - every other member of their extended families had been murdered.

Friend was a student activist in Bs As during the dictatorship and had to go in hiding for extended periods; several of his classmates and friends were disappeared and murdered in turn. I hate to think what his survivor parents must have been dreading. Around 10% of the murdered disappeared were of Jewish heritage.

A LEXICON OF TERROR

Argentina and the Legacies of Torture.

By Marguerite Feitlowitz.

Illustrated. 302 pp. New York:

Oxford University Press. $30.

This is in "Nelligan", the Montréal library system.

He is much more serene now, by the way, with the same sardonic wit and intense activity.

I was touched to see Treblinka as well as Auschwitz, and grateful for the restored cemetery in Warsaw.

kseniaprints says

This really moved me! Thank you for taking the time to read my musings and to comment, and I'm pleased to read it brought back some memories of your friend, albeit not in a pleasant context

Susan Marks says

Hi,

My family also came from Kulchiny. My grandfather emigrated to U.S. in 1906 and my grandmother in 1915 or so. The last name was Marchbein. When I look up his last name at Yad Vashem, it seems that they were all killed when the Nazi's marched through. I am always interested in info about Kulchin, and durvibors.

Cher says

Your experience in Poland was so touching. I was also there last year.

Modern day Poland has very good museums on the Jewish people --also very moving. So many sad stories

Thanks for sharing.

kseniaprints says

It's incredible to see the reckoning that Poland has done with its past, and seeing the Jewish history museum POLIN was incredibly moving. Thank you for reading, and sharing your experience.